Money & Monitoring

As with many of the Toolkit sections there is a lot to absorb here. We advise newcomers to read it all but here’s a click-able list of the main sections:

- Managing on Low Resources

- Look After The Pennies…

- Motivation & Stress

- Basic Financial Management

- Finding Core Funding

- Cashflow and Overdrafts

- Monitoring and Evaluation

- Evaluation and Audience Research

Authors note 2014 – this section was written before the economic crash and the current period of ‘austerity’ – but its advice on funding and project management are as relevant now as it was then.

Managing on low resources

Community radio is a greedy beast. However many resources – financial, material, human or supportive – you may have at your disposal, a community radio project will swallow them up, burp and ask for seconds. A 24 hour commercial radio station might typically employ 30-40 full-time staff, and a community station is attempting to produce a similar volume of output with many more broadcasters to manage, not to mention a host of additional social and pastoral responsibilities, with perhaps 10% of that number. The demands for equipment, facilities, marketing resources and administration costs are endless. What’s more, community outreach work, education, training, volunteer development and other social gain-related activities tend to be self-generating – the better you are at doing them, the more people will seek your help. Sooner or later you have to draw a line under your spending, and that will usually be at almost exactly the same moment that your money is about to run out. The question is how you can get the best results from the least expense.

Look at the big picture

While good management of a well-designed project can sometimes generate miraculous results from minimal resources, it is important that you give yourself a realistic chance. The overwhelming majority of station costs are entirely predictable. Hypothetically, if a station has an annual turnover of £100,000, as much as £95,000 may be predicted in advance.

Expenditure can be categorised as ‘fixed’ or ‘variable.’

- Fixed costs – Whatever you cannot change: Rent; business rates; insurance etc.

- Variable costs – Staff costs; some bills (especially telephone); emergency repairs; special events; stationery; marketing etc.

Like your expenditure, your income can also be described in different ways:

CRIB SHEET

When managing your station remember that:

- Your resources are never as plentiful as you need

- Your spending is mostly fixed and predictable

- Your resources may come from earned income, core funding or project funding

- General income – Money which can be spent as you see fit. This may come from general fundraising, business activities (e.g. selling advertising or services) or untied donations.

- Core funding – Money you are given to keep your station running, so covering your basic costs of staff salaries; premises etc

- Project funding – Money which is provided for particular purposes, such as broadcasting a particular message or conducting outreach work with a specific section of the population.

While the vast bulk of your station income will go on staff salaries and fixed costs, it is often the apparently trivial budgets that cause most anguish. When a studio CD player breaks and there isn’t £100 spare to repair it, the stress and inconvenience caused can be out of all proportion to the money involved. We will return shortly to the larger picture of budget management, but first we’ll consider ways to keep your variable costs down.

Look after the pennies…

With several over-worked members of staff and dozens of enthusiastic volunteers coming and going at your station, it is incredibly easy for the petty cash supply to be eaten up, whether literally in the shape of chocolate-covered Hob Nobs, or metaphorically with a ready supply of blank mini-discs or stamps. At Radio Regen we try to avoid the use of petty cash altogether – maybe it’s just us but it NEVER adds up at the end and the time and aggro expended in trying to track down that missing receipt for teabags is just not worth the sums involved. Instead we use an expenses system pump primed by an advance to those staff who buy a lot of teabags

Someone at the station needs to make themselves deeply unpopular with their unashamed stinginess. While you really should supply your volunteers with a sack of teabags from the cash and carry, if they want to drink Lapsang Souchong they can bring their own. Keep an eye on the itemised bills and try to instil a culture of cost-awareness at the station – small details such as switching off lights and equipment in empty rooms or not filling the kettle to the top every time it is boiled will actually make a noticeable difference to the year’s electricity bills and will be a constant reminder to everyone at the station that money is tight (plus maybe saving an inch or two of the polar ice cap). There’s nothing as sobering as explaining that replacement ‘pop’ shields cant be bought because the station spent too much on Lapsang Souchong .

Make sure that all volunteers understand that if equipment is lost or damaged, it cannot always be replaced. Focus people’s minds on the need to treat every microphone and every machine with utmost care and respect. Above all, keep a very tight eye on your phone bill. This is the one expense that can suddenly rocket, if someone at the station – whether thoughtlessly or selfishly – makes some long calls to a mobile phone or overseas (our record at Radio Regen was a £57 call made to the Congo) . You may want to consider blocking such numbers on the station phone, if you can.

Never pay for anything you can get for free

One of the great strengths of community radio is that people want to help. A station manager needs to be utterly shameless in asking for favours, donations or freebies – just remember “It’s for charidee!”. If your team of volunteers includes a joiner and you have a broken door, just ask. (see VoxBox ** below) If the volunteer is happy to use her skills to help you out, that is fantastic. But always be gracious with refusals – it is not fair to pressurise someone into working for you for nothing, even if they do get a show once a month.

Check whether there is any form of LETS (Local Exchange Trading Scheme) or time bank operating in your area. These schemes allow individuals and groups to trade skills and services for tokens instead of cash, and as a radio station you have a lot to offer. You could, for example, run a regular slot about services needed and offered on the scheme on your community programmes, in return for an agreed number of tokens which could be traded in for maintenance work or other basic favours.

Some newcomers to radio imagine that buying music is a major cost for radio stations. In fact there should be no need to spend a single penny on them. Record companies employ publicists (either on their own payroll or contracted specialists, called ‘pluggers’ in the trade) specifically to send new releases to radio stations. At present some record labels are more willing than others to include community radio stations on their mail-out of new music. Some are yet to be convinced that a community station is anything more than a hobby project or pirate. As the sector grows in volume and profile we would hope this should change.

Small independent and specialist labels might not routinely send out promotional music, but they also tend to be flexible, if your station is offering to publicise their music for free. As ever, if you don’t ask you don’t get.

VOXBOX**

“The building we are in now was an old boatshed that we renovated. When we first came in there were no partitions, no doors, no floorboards in some places. It was horrendous. We had a lot of help – many of our volunteers are tradesmen, plumbers, joiners and so on, They helped us, and we give them some advertising, so it benefits them as well as us.”

Kathleen MacIver, Station Co-ordinator, Isles FM, Stornoway.

Never do something for free if you can get paid

With your place at the very heart of your community, you will regularly be approached by other groups, agencies, businesses, charities etc, all of whom want you to do things for them, whether it’s broadcast a message, publicise an event, or borrow your facilities. There is always a temptation to say yes, especially to well-intentioned community projects or charities. But don’t assume these groups are completely cash-strapped. Their staff have probably read a similar book to this one and are following the maxim above: ‘never pay for anything you can get for free.’ Don’t be embarrassed to ask them if they have a budget available for publicity or hire of facilities. If they have, then you are entitled to your share. If they haven’t, you may well end up agreeing as a favour anyway, but try to get an assurance that the favour will be returned in some way at a later date. If you are offering a service to another group you may wish to try a pilot scheme first for minimal or zero charge, but be clear what is being offered and for how long. If the arrangement is to continue, then you are entitled to be asking for payment.

Asking for payment from like-minded groups shouldn’t trouble you – they can always say no, and you’ll be no good to them if you go belly up by being too generous with your services. Even if nothing comes back to you, the request is a way of placing value on the services you offer.

VOXBOX **

“A woman from a funding agency visited the station for a meeting early one morning, and when she arrived I was doing the hoovering. My colleague introduced us and we chatted for a bit. Then she asked me what my job was and I told her ‘station manager’. She looked really puzzled, and asked ‘so why are you doing the hoovering?’ I answered, ‘because the floor was dirty.’

Alex Green, Station Manager ALL FM.

The nature of a community radio station is that everyone tends to muck in together. If you save money by not hiring a cleaner, it is incumbent on everyone to do some cleaning occasionally (see VoxBox**) . More seriously, a large number of tasks required to run a station fall outside the particular remit of any one member of staff. The words ‘someone else’s problem’ or ‘more than my job’s worth’ should never be uttered at a community radio station, everyone needs to support everyone else and one person’s problem is everyone’s problem.

…but not too much.

It is very easy for staff members to get sucked into a tornado of minor tasks – nailing down loose carpets, hoovering (!), settling personal squabbles, undertaking lengthy face-to-face support with troubled volunteers etc. It is crucial that paid staff remember what it is they are being paid to do. Your station will thrive or struggle according to your performance in your key

CRIB SHEET

When your financial and other resources are tight.

- You must keep an eye on petty spending and bills.

- Never pay for anything you can get for free.

- Never do anything for free if you can get paid.

- Your staff and volunteers will be stretched – everyone must remember their job.

tasks. If an employee is being paid to conduct outreach work and liaison with other community groups, then that is what he should spend his time doing. If he can do that well, and still have time left over to help a volunteer make a jingle then so much the better, but the work must be prioritised.

Motivation and stress

It shouldn’t be difficult to motivate your workers and key volunteers. Community radio changes people’s lives for the better, and you can see it with your own eyes and hear it with your own ears. Nevertheless there are times when things have been running less than smoothly, tempers are getting frayed, workloads spiral out of control and morale begins to dip. With anything up to five years of radio looming ahead of you, there are very few end points in a community radio project, those moments you can sit back and applaud yourselves for a job well done, evaluate your performance and plan it better for next time. Typically a community radio station might have several dozen projects running simultaneously, consecutively or overlapping, and inevitably it will often feel as if everyone is playing ‘catch-up’ for most of the time.

VOXBOX

“Don’t tune into the station all the time. It was an addiction I fell foul of when I first got into community radio. It made me very anti-social, because even if I was at home and had friends round, I would have the radio on, and wouldn’t be engaged in the conversation. I’d be talking to a friend with one ear on the radio and suddenly – ‘Hang on! What did he just say?’ Eventually my partner threatened to throw the radio out the window.”

Phil Korbel, Director, Radio Regen

People can react to stressful workloads in several ways. Some will do as much as they can, accept their own limitations, and sleep soundly at night. Others will look at their in-tray and think ‘I’ll never do all this, so what’s the point of doing anything?’ In such cases it is crucial that their line manager intervenes, either with an inspiring motivational pep talk (or more effectively, lots of little ones) stressing the employee’s skills and talents and underlining how valuable they are to the station. More practically, re-negotiate their workload, or break it into smaller chunks with attainable targets, so it looks less intimidating. Many people work harder when they have less to do. Of course, it is preferable to give people compliments, encouragement and manageable workloads before they begin to despair, not after.

The other response someone may have to a large workload is, if anything, even more dangerous: to try and do it all. Many community radio workers and even volunteers will be so motivated and enthused by the project that they never leave work.

CRIB SHEET

Motivation

- Is essential to run a community radio station

- Can lead to exhaustion, stress and burn-out

Or when they do, their thoughts (and radio) remain tuned to it (see VoxBox). This is simply unsustainable – the demands a community station can make upon you are literally endless. The result is stress, exhaustion, illness and eventually a letter of resignation. We have learned to our cost the harm which burn-out can cause to individuals and stations.

Spotting stress and burn-out

Preventing stress and burn out is in your own interest if you want to sustain a good staff team, but it is also your legal obligation, under Health and Safety at Work laws. Stress affects different people in different ways, and there are no hard and fast rules for how people will react, but keep an eye out for the following clues in your colleagues and yourself:

- Illness and absenteeism. Stressed people get ill more often as their immune system is weakened. Especially look out for regular headaches, back or muscular pain, palpitations or chest pains and stomach upsets, all of which are commonly (although far from exclusively) stress-related.

- Sleep problems. If you can’t sleep at night for worrying about the Myriad automation system, alarm bells should be ringing.

- Anxiety, depression, panic attacks, or (less seriously) irritability and a changing attitude or demeanour.

- Low energy levels and tiredness.

- Conflicts in personal life and relationships

- Changing drinking habits or intake of recreational or prescription drugs.

- Adrenaline addiction. People can get hooked on the buzz which accompanies stress. If someone seems to be deliberately seeking out demanding projects and extra workload, ask yourself why.

Just as different people react to stress differently, so different people need different strategies to keep their stress levels down. Here are some useful pointers:

- Avoid a stress culture at work. It is easy for a pattern to develop at a station where the staff work 12 hour days, come in at weekends, and spend their evenings at community meetings. If one or two employees act like this (especially management) it can easily become seen as the norm, rather than the exception, and others will feel obliged to match up. Senior management should set a good example by knocking off early to go to the pub. Occasionally.

- If you know there’s going to be a series of late nights or weekend work sessions for a specific project put a limit on them and take back the time owed before you forget why you did the extra hours – by booking in the time off when you book in the extra shifts.

- Watch your flexi-time and holiday records. If a member of staff has built up 90 days of flexi-time or has only taken two days holiday in six months, their line manager should really intervene and send them home. The term for this is ‘present-eeism’.

- Have a laugh. Laughter relieves tension which in turn reduces stress. Make sure your workplace is a fun place to come in to each day. Within limits, obviously (and nervous laughter or laughing at nothing doesn’t count).

- Make the station as neat and comfortable as possible. Not necessarily sofas in every room, but try to reduce clutter and chaos, which is a significant contributing factor to a stressful environment.

- Manage your time. Time management is crucial to a relaxed working environment. Make sure your deadlines, targets and projects are spread as evenly as possible through the year, and learn to organise your days and weeks.

- Manage your money. If you can keep on top of your budgets, cashflows and accounting, everything will be much, much easier.

- Deal quickly and effectively with personal disputes and arguments that develop between staff or volunteers.

- Have a quiet space where staff can retreat to work in peace or catch their breath over a cup of tea or coffee. But…

- Reduce your caffeine. High caffeine consumption increases the heart rate, as does stress. The two together are an unhealthy and unhelpful combination. Caffeine also makes it harder for you to unwind and sleep at night. Remember many fizzy drinks contain more caffeine than a strong cup of coffee. Some smug staffers at Radio Regen swear blind they’ve never had as much energy since they dumped caffeine that’s my middle name!.

- Leave work at work when you leave. Maintain other interests and find time to do whatever makes you happy – so long as it has nothing to do with radio. Leave plenty of time for long soak in the bath at the end of the day.

CRIB SHEET

Stress and burn-out

- Can be seen coming

- Can be eased or avoided

- Compartmentalise. Do what you can in the time you have to do it in – prioritising and planning your work to maximise your efficiency. However motivated and efficient you are, there is only so much you can do, and if you start to lose sleep as a result of that inevitably overflowing in-tray you’ll only get less work done. So put your work in a mental compartment and make sure that there are other compartments in your life that are important to you – they might be the ones that keep you sane.

- Never give out your home or personal mobile number. If you have an emergency staff contact procedure, get a dedicated phone and have a formal rota for shifts on-call. Try to make colleagues and volunteers understand that emergencies do not include such disasters as running out of sugar.

Basic financial management

There are two principle strands to financial management:

- Budget management.

- Projecting income and expenditure. Your OFCOM application form will have spelled out in broad terms where you expect to find the money it will take to run your station

Budget management

You need to ensure that the money you are spending at the station, day-by-day and month-by-month, is affordable. A community radio station may have dozens of different budgets operating at once, and every penny that is spent needs to be subtracted from one of them. There should also be a receipt or invoice filed against every expense. If ever you think this is onerous, summon the mental image of a steely eyed auditor from Government Office descending on you and asking to see your audit trail – it will happen to you. Before you ‘go live’ ask your accountant to help you set up a basic system to help you do this. They really shouldn’t charge you (much) for this as it will make their job so much easier when they come to do your books. Tell them it’s a good will gesture as we’ve heard some accountants actually have this in their vocabulary.

The opportunities community radio offer are so extensive, that staff members and volunteers will always be coming up with brilliant ideas, which ‘won’t cost much.’ They soon add up to a large hole in station funding. The one question that station managers need to ask their colleagues more than any other is… ‘and who will pay for that?’

To keep track of what money is being spent against which budgets, you should probably use some computerised accountancy package. It is possible to keep track of income and expenditure using simple spreadsheets, but it can invite confusion and errors. The money (and time) required to learn a basic computerised system would be an excellent investment. Quickbooks is one industry standard that your accountant will understand.

Projecting income and expenditure

In our experience it is practically impossible for a community radio station ever to have all of its annual core funding in place at the start of each financial year – never mind for the next five years. OFCOM don’t expect it, and neither should the Board. Obtaining funding tends to be an ongoing process, with bits of money arriving here and there through projects, grants, fundraising and various windfalls.

To prevent this leading to serious financial problems, the finance manager needs to be able to identify not just how fully-funded the station is today, but how under-funded it will be in several months time. Good financial planning you will enable you to see budget shortfalls coming long before they arrive, giving you plenty of time to look for alternative streams. So if you are looking ahead over a full year and still have a shortfall of perhaps 25% of your turnover, you needn’t panic. At the other end, if you are looking only three months ahead and cannot see how staff wages are going to be paid, then a crisis meeting – if not full blown panic – is probably in order. That is still far preferable to suddenly finding your cheques bouncing.

Matching resources to tasks

As we explained in the previous section, you can get the most out of your resources with a well-motivated (but unstressed) team of staff and volunteers and a careful eye on the purse-strings. But that should not detract from the need to have a well-financed project with resources that are (at least nearly) adequate for the tasks you have set yourselves. Your initial OFCOM licence application should be realistic about what you hope to achieve and how it shall be funded , and that includes stating what staff positions you intend to fill.

The premises you choose can make a difference to your core costs, of course – if you can find a community centre which can provide enough space to host your station for a minimal rent then you give yourself a head start, financially. But of all your variable expenditure, staff salaries are the most flexible. If you find yourself short of £15,000 in the coming year and cannot find funding to cover it, the only way you can realistically save that sort of money is with a redundancy. However that will inevitably impact on the ability of the station to match objectives set by OFCOM or your funding agencies. It’s also a poor way to run any form of enterprise, if staff do not feel their position is secure they are unlikely to show the dedication, commitment and motivation you will need from them. And besides, the law ensures that in most cases it’s pretty difficult for an employer to simply click their fingers and dismiss employees.

The secret then, is to ensure you can find enough resources to do what you have promised to do.

Finding core funding

Core funding is the money you will need to keep your station running – salaries, rent, bills etc. It is obviously essential to any community radio station. Many funding agencies are reluctant to pay core costs, and only offer ‘project funding’ to pay for specific activities or functions. When you are getting your funding in place, if you don’t include claims for core funding you could find yourself awash with cash to perform particular functions, but without a studio or station to work in.

Some community stations have a parent group or charity (such as an existing community centre) which can guarantee core funding. They are lucky (if less than fully independent). If your core funding is in place, or you have a realistic strategy to find it, you are well on the way to running a successful community radio station. If you don’t you could find yourself on a rocky path.

When applying for grants from funding agencies, you should always seek core funding. This may mean a funding application which includes staff time for administration; management; technical support etc. This is complicated, but necessary. Say funding is available for a project to broadcast health advice to young mothers. A part-time outreach worker’s salary is included, plus a budget for materials. But that part-time worker has to be supervised, taking up the time of a line manager. That should also be funded. The project takes over the training room for two hours a week, meaning it can’t be used for other – possibly lucrative – sessions. The engineer has to maintain the studio when things go wrong, eating into his time and workload. And so on, across the station.

CRIB SHEET

Core funding

- Is different to project funding.

- Is harder to find than project funding.

- Is absolutely crucial to financial management.

Even a small project might take up a few hours a week of every physical resource and every member of staff, so the application should include that as well as the ‘headline’ project worker. If funders refuse to comply with such reasonable requests, you should seriously consider declining the funding. The project could end up costing you more than it is worth. Some funders, such as the Big Lottery Fund, are now talking along these lines (calling it Full Cost Retrieval) but at the time of writing their sister organisation Heritage Lottery Fund point blank refuses such budget lines in some of their applications.

A community radio group might consider themselves lucky if they find a single source of funding which can cover 50% of annual income (the maximum allowed by OFCOM). However there are advantages to several smaller funding streams running simultaneously – funding would usually be more staggered, which helps cashflow, and if one source dries up, it is unlikely to close the station. Multiple funding streams also help your independence should a major funder seek to exercise undue influence.

Cashflow and overdrafts

Cashflow is one of the biggest headaches for any community project. It is reasonably straightforward to calculate how great your expenses will be over the next financial year and also that you can raise enough money to cover it all. But if the money isn’t going to reach your bank account for another six months, what will you do to pay staff wages next week?

The solution is to plan not only how much money you will receive, but when you will receive it. The secret of healthy cashflow is getting the money in before it goes out. Unfortunately that is often easier said than done. Payments from funders and partners can fail to arrive when expected, or you may only secure some of your funding at the last minute. If you have a concrete picture of when what cash is hitting the account, don’t be afraid of spending money for project X on staff for project Y – so long as you are sure the reverse happens and the books balance at the end of the accounting period for each project. Also, some funds insist that you spend their money on the items you detailed in your application – some couldn’t care less what you spend it on so long as you deliver their outputs. The result of the latter is that if you happen to come in under budget, any surplus is yours to use elsewhere on the station (more Lapsang Souchong perhaps.)

CRIB SHEET

Cashflow

- Needs to be carefully managed

- Is very difficult to manage without overdraft facilities

The traditional remedy for cash flow problems is an overdraft at the bank. Unfortunately many banks – even those which make ethical and social responsibility claims – will flatly refuse to offer such facilities to community and voluntary groups. Sometimes even waving a promissory letter from a major funding agency will not budge them. It is worth bearing this in mind when first opening your bank account. If you go to a bank manager offering him an account with a £100,000 annual turnover, you are negotiating from a position of strength. Insist upon overdraft facilities as a condition of opening the account, and you will often find banks are more flexible than they first claim.

Another option is to talk to a major partner in your station, such as the local council or college and see if they might forward you your running costs against guaranteed grant income. It costs them nothing and it enables them to have a role in facilitating a vital service for their community. You’ll never know if you don’t ask and they might even say yes.

Monitoring and evaluation

When running a community radio station, it is not enough to make great improvements to your community and the lives of your volunteers. You have to be able to prove you have made those improvements – to your funders, to OFCOM, and not least to yourselves. The way you do this is with project monitoring (recording exactly what is done or ‘what we did’) and evaluation (making judgements about the information recorded or ‘was it any good?’)

It’s very easy to get caught up in the exhilarating side of community radio – making programmes, training volunteers, working with dynamic community groups. But unless you make a good job of the rather dry business of recording your activities, your funding will soon dry up and it will count for nothing. If you approach it in a calm, organised fashion, it need not be a painful process.

There are two areas which funders will want you to account for yourself:

- Spending – have you spent the money as you promised you would?

- Performance – have you achieved what you said you would.

In most cases your accounting system should take care of the former. Your annual audit of accounts will require you to keep a paper trail to record every item of spending, and each of those should have been apportioned clearly to one budget.

It is your performance monitoring that is likely to prove more problematic. Typically, a community radio station will need to be able to answer the following questions to a variety of funders:

CRIB SHEET

Project monitoring:

- Is how you prove you are doing as you promised

- Is an essential chore

- How many individual volunteers have used the station and how much?

- How many volunteers have been through training schemes, and which ones, with what duration and with what results?

- How many volunteers and trainees belong to specifically targeted sections of the community (e.g. with disabilities, from particular deprived wards, from specific ethnic groups etc)?

- How many (and which) community groups have been helped?

- How many other visitors have you had to your station, and to what purpose?

- How many local businesses have been helped and how?

- How many schools have participated and how?

- How many jobs have been created or safe-guarded?

Strangely, in six years of community radio monitoring for dozens of different funders, at Radio Regen we have never once been asked to report on our broadcast output. That is perhaps a useful reminder of the relative importance of community and radio activities, at least as far as funders are concerned.

Plan ahead [or Find out what they need to know in good time]

Before you even accept a grant, you should read the small print. What information will the funder need back from you? Some want only quite general statistics and outcome measures, others will ask for extensive detail. The amount of monitoring required often shows little correlation to the size of the grant involved, and in extreme cases you may judge that a grant of a few hundred pounds is not worth it if you have to report back every volunteer’s height in centimetres and their grandmother’s maiden name.

Assuming you’ve taken the cash, begin collecting the information you need at the very outset, and continue as you go. Much of it may have already been collected, so ideally, you should collect all the information you might reasonably need about your volunteers when they first sign up – age, sex, employment status or occupation, education, disability, illness and access information, ethnic origin and so on. You then require volunteers to sign in and record the nature of their activity each time they visit the station. Just that simple system will cover many of your monitoring needs.

However you organise it, try to ensure that volunteers and partners aren’t being asked for the same information repeatedly on several different forms – if for no other reason than they will become much more reluctant to fill in any of them. It is already hard enough getting many volunteers to sign an attendance sheet. There is also the vexed question of letting the volunteers know why you need the information without giving the impression that you are being paid as a results of their work making radio on the station. Far fetched? It’s happened to us. Better to say that without that information the station closes – it needs to be second nature to volunteers.

CRIB SHEET

The information you will need for monitoring:

- Should be considered when accepting funding

- Should be recorded from the beginning of a project, not once it’s over.

The ideal would be a single data collection questionnaire which volunteers could complete once and then update with every activity session and at the completion of the project. In practice, at Radio Regen we have yet to design such a form satisfactorily, and we have the piles of paper to prove it.

Many grants will have their own unique conditions attached. Be quite clear what they are from the outset and get them agreed in writing. There is nothing worse than having to track back through six months of station activities because a funder has suddenly decided they need to know whether a volunteer was supervised by a trainer for 25% or 50% of their studio time and the information was not recorded at the time. We cannot stress enough how vital it is to be clear exactly what monitoring you will need to conduct before you begin a project. It can be just about impossible to do it retrospectively.

Evaluation

Monitoring is the process of recording what you do for the benefit of others – usually funders. Evaluation is what you do for your own benefit and sometimes for funders, to improve your performance as a station, and it is another task that is easily forgotten about. Perhaps you are obtaining results which look great on paper and tick all the relevant boxes for your funders and OFCOM alike. But what do your volunteers think? Are they bored by your training, unhappy with your schedule and alienated from each other and the staff? What do your listeners think? Do you even have any? Evaluating your performance is key to identifying your shortcomings and failures and building on your achievements and strengths.

Everything you do must be constantly measured against your stated intents as a station. If your mission statement says you are going to change the lives of local residents, ask yourself how much change you see around you, and whether your day to day activities are responsible.

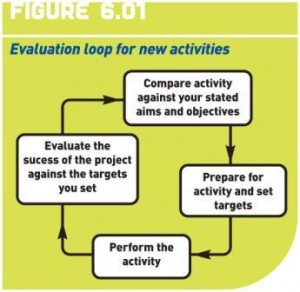

One popular way of thinking about evaluation is as a spiral (or more simply) a loop (see Figure **). Every time you consider beginning a new project or changing your activities at the station, you should compare that activity against your stated aims, prepare for the activity and set targets, perform the activity, measure the outcome and compare to targets, review and evaluate the performance, then compare the results to your stated aims.

Although in theory that looks complex, in practice it is mostly common sense. Here’s a purely hypothetical example. You spot some grant money available to increase the profile of over-65s in the media. What happens next?

Although in theory that looks complex, in practice it is mostly common sense. Here’s a purely hypothetical example. You spot some grant money available to increase the profile of over-65s in the media. What happens next?

- You ask yourselves whether this fits in with the core objectives of your station and whether or not to begin the loop.

- You plan outreach work and training aimed specifically at that age group, and set yourselves targets for recruitment, training and broadcast hours.

- You apply for and receive funding, recruit and train volunteers and they begin broadcasting their own show every Tuesday.

- You examine your monitoring data and evaluate the project against the targets you originally set yourself (and that you agreed with the funders.)

- (and 1.) You ask yourselves whether the project (in practice) fits with the core objectives of your station and whether or not to continue.

If the organisational culture is to routinely think about activities in this kind of way, evaluation quickly becomes an integral part of your station, rather than an additional chore.

Evaluating your audience

Anyone involved in a community radio station will confirm that when you meet someone and tell them you are from a community station, the first question they ask is ‘so do you get many listeners?’ The usual answer is, ‘erm, we don’t really know.’

Ironically, it is one of the few questions that OFCOM don’t ask. Community radio (thankfully) is not about chasing every listener at the expense of other social gain targets. However there will come a time when you need to get some idea of who is listening. Some funders might insist upon asking. If you intend to sell advertising or sponsorship to any significant extent then your clients will certainly want to know.

BBC and commercial radio stations find out their listings from a company called RAJAR (actually co-owned by BBC and the commercial radio network) who use sample surveys to calculate how many listeners each station has. Community radio stations are usually too small (geographically) to obtain remotely accurate results using RAJAR even if you could afford their fees.

You will have some idea of the popularity of your station from the feedback you get anyway – the phone calls, emails, website hits and so on. You should invite such feedback at every opportunity. If you are brave you could hold public meetings on a regular or sporadic basis where you invite your listeners to come and tell you what they think. Be warned, it may not always be an entirely inspirational occasion – it’s human nature to want to complain about what we don’t like before we applaud what we do. Nevertheless it can be a highly enlightening and useful process – assuming of course that you take the feedback on board and use it to improve what you do.

Ultimately there is no substitute for well conducted research among a random sample of your community. There are many market research companies who would gladly conduct a survey in your specific area. The costs are generally extravagant, but if you are bringing in large sums of money from advertisers it may be worthwhile. That way there will be a certain credibility to the figures.

In practice, you will probably end up doing it yourself, or if you are very lucky, persuading a school or college to take it on as a class project in social sciences, media studies or statistics. An audience survey would normally either be done using a phone and a directory, or a clipboard and a smile.

Another approach when asked about your listening figures is to reply that you know what you do works – that the partners you work with want to continue their partnerships and that volunteers keep coming back to do their shows. They wouldn’t do it if something wasn’t working. Some ‘user testimonials’ are always useful to back up this line of argument.

Designing your audience research

First of all you must ask yourself what it is that you want to know. Do you just want to know the raw number of listeners you have, or the proportion of radio listeners at any one time? Do you want to know what the listeners think of you? Which sections of the community like you more – by age, sex, social class or ethnicity? Do you want to know which parts of your schedule are more or less popular? Do you want to know why those who don’t listen to you choose not to?

All those questions are valuable, but remember that the more questions you ask, the more data you will have to analyse, the longer it will take to conduct the survey and the harder it will be to persuade members of the public to participate. Keep your focus on what you really need to know.

Ideally an evaluation questionnaire should be written and delivered by people with no vested interest in the station. It is easy to skew the results by accident or design – to take a silly example, a researcher can ask the question: ‘would you say your local community radio station was A/ Interesting B/ Fascinating or C/ Amazing’ then report back how wonderful everyone thinks they are.

CRIB SHEET

Audience research is;

- Useful but not crucial

- Hard to get

- Easy to manipulate if it is not independent

- Possible to do well, and easy to do badly.

More seriously, the psychology of market research is very subtle. You can actually change the results of surveys by changing the wording of questions or even the order in which you ask them. So if a survey were to start off by listing all the station’s social gain achievements and asking whether the interviewee thinks each one is a good thing or not, the effect is to make the interviewee feel more supportive and positive about the station, making it more likely they will say nice things on the later questions. Such flaws often creep into market research unintentionally, and they can work against you just as often as for you.

Make sure that any data you capture is useable – by avoiding the general recording of comment and by using multiple choice options that enable you to extract those vital percentages.

While it may be tempting to try to manipulate results by framing the questionnaire in a particular way, audience feedback is incredibly useful to community radio, and you will find the value of getting accurate results is much greater than the value of getting positive results. Hopefully you will get both.